On the evening of the best day of her life, Adrienne Bunn crossed the finish line at the Ironman World Championships with her arms raised and a beaming smile as she high kicked, stomped her feet with intense pride, and ran to celebrate with her waiting family.

In her excitement, she nearly tackled her dad. She hugged her mom, who placed a Kukui nut lei around her neck, a Hawaiian tradition symbolizing pride and celebration. She squeezed her older sister, whose face was soaked with tears.

Adrienne, the 18-year-old girl from Florida with autism, had just completed one of the world’s most challenging endurance races: a 2.4-mile ocean swim through the choppy waters of Kailua Bay, a 112-mile bike ride through the volcanic hills of the Queen Ka’ahumanu Highway, and a 26.2-mile run through Kona’s rugged terrain to cross the finish line. All the while battling the heat and humidity that zap your energy. In doing so, she became both the youngest known female athlete and the first woman with autism to complete the Ironman World Championship.

Adrienne Bunn doesn't concern herself with labels. [Courtesy photos]

Her excitement said it all. This was more than simply finishing a race. This was an iconic moment in the annals of sports history, one that transcends competition, not because Kona challenges the world’s best athletes, but because for a girl with autism, one who to this point had never attempted a full Ironman, who had to push past the sensory overload of the crashing waves and speeding cars, and who relied on a unified partner to guide her to the finish, it might as well have been completing the impossible.

Then again, Adrienne Bunn doesn’t concern herself with labels. She’s been told by outsiders her entire life what she can and can’t do. And frankly, she doesn’t care much for others’ opinions. Because the finisher’s clock proved what doctors and doubters said she could never do:

Adrienne BUNN: 12 hours, 41 minutes, 18 seconds.

Adrienne was diagnosed with autism at 4 years old, a condition that shaped how she saw, heard, and felt the world. That means loud noises can feel overwhelming, routines are important, and an unexpected change can feel confusing or frightening. Navigating a world of negativity wasn’t easy, especially for her parents, Bob and June, who wanted to protect her from people’s harsh words and rude stares.

So when Adrienne didn’t speak until she was 4 — although she was known for babbling plenty — June was quick to chime in when other kids began making fun. And at home when Adrienne felt overwhelmed and frustrated, like the world was closing in, her parents gave her space to unleash her emotions that she didn’t know how to express.

After her diagnosis, they found refuge at a local equine center that provided specialized therapy for children with disabilities. Adrienne bonded with the biggest horse on the farm: a black draft horse named Ernie.

“They’re very gentle and very nice to hang around with,” Adrienne says. “They’re kind of like dogs. They know when you’re tired, they know when you’re stressed, they know when you’re angry. When I’m with them, it’s so nice and relaxing.”

While horses provided peace that boosted Adrienne’s balance, speech and confidence, school proved a torment. Teachers and administrators complained that Adrienne couldn’t stay seated and was a disruption to the class. June and Bob moved Adrienne in and out of schools. By the third one, the head of the school asked if they would be willing to put Adrienne on medication to calm her.

No, they didn’t want to, but there was no roadmap to follow. And weren’t the administrators looking out for what was best for the kids? They relented.

June and Bob knew Adrienne had a lot of energy, and expending that energy helped her mood. Sometimes when Bob was working in the yard, he’d ask Adrienne to pick up five acorns. Instead, she picked up every one she could find. Other times they would time her as she ran around the house. Adrienne ran endlessly until they told her to stop.

“Then we realized, ‘Okay, that’s how you’ve got to expend your energy,’” June says.

Once on the medication, though, Adrienne was a shell of the energetic child they once knew. One day, June found Adrienne drooling on herself. That’s when mama bear snapped: no more meds.

“It was just like, ‘Are we doing this for us or for her? This is so wrong,’” June recalls. “And so, we started weaning her off.”

Coincidentally around the same time, the school’s P.E. teacher had the students run around a parking lot. For every mile they ran, they received a charm shaped like a foot that they could put around a necklace as a token for their mileage. It wasn’t long until Adrienne had a necklace full of feet.

A coincidence in Adrienne’s life may explain one moment, but with another stroke of luck, it started feeling a bit more like fate.

After collecting all those feet charms, Adrienne heard from the Florida director of the Special Olympics. They were starting a pilot program for a sprint triathlon and looking for athletes. Was Adrienne interested?

First of all, yes. Secondly, what’s a triathlon?

“We were starting with no knowledge,” June says. “I didn’t even know what a triathlon was. Like you do all these events on the same day? So we’re explaining it to her and she’s game. She’s like, ‘Yeah, I’ll do it. Do I get to be with (other people)?’ The social aspect was what motivated her. The physical aspect has never been an issue — ever. It’s always been finding a place for her.”

At 13, Adrienne was the only girl amongst a group of three boys to train for a half-mile swim, 12.4-mile bike ride, and 3.1-mile run. Surrounded by other neurodivergent athletes with coaches who had patience in training, Adrienne soared.

It was also a blessing for mom and dad, who also found a community of parents who understood their struggles and frustrations.

“If she didn’t have running and she didn’t have her own outlets …” June says, not finishing her thought. But her silence says what her words don’t.

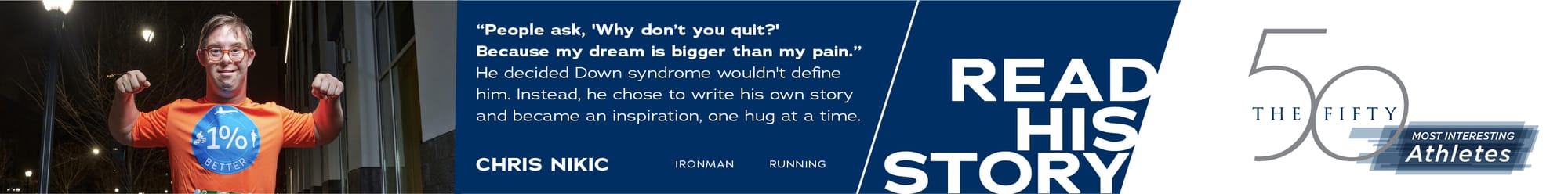

I first met the Bunn family in 2023 in Atlanta. I was reporting a profile on Chris Nikic for The FIFTY. Coincidentally, Chris was one of the athletes who joined the same pilot program. Chris is the first person with Down syndrome to ever complete an Ironman, in 2020, proving to the world how neurodivergent athletes can have active, healthy, fruitful lives.

Chris had received plenty of national acclaim when I met him, but what I found most interesting was how he and his father, Nik, were teaching other neurodivergent athletes to set, chase and achieve their own goals. Nik developed a 1% Better program for Chris with the simple premise: If Chris got 1% better each day, what could he accomplish? The two also partnered with Adidas to create Runner 321: a call for every race worldwide to reserve bib number 321 for an athlete with a neurodivergent condition. (Chris has since ran all six major marathons worldwide to raise awareness for Runner 321.)

The Atlanta Marathon was the first non-major marathon to do so, which is why Nik brought a group of runners to Georgia to compete in the various races, Adrienne among them.

Adrienne found a love for running in elementary school and hasn't slowed down. [Courtesy photos]

Though I was there reporting on Chris, I spent a lot of time with other families, hearing their exhaustive stories about how they were told their children would amount to nothing — until they found sports and flourished.

One morning at the hotel breakfast bar, I sat with Nik and Bob. Adrienne was nearby with Chris and their other friends. As Nik, Bob and I spoke, I couldn’t help but admire the camaraderie between the group as they watched highlights on SportsCenter and ate breakfast.

“I’m a UF fan,” Adrienne said, referring to the University of Florida. “I cheer for the Gators.”

“They suck,” Chris quickly chimed in.

“Their coach is garbage,” said Johnathan Sady, a fellow runner with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

The comment clearly riled Adrienne, like it wasn’t the first time either of them made such a remark.

“No! That’s a lie,” she said.

Nik broke away from our conversation to join in the banter. “After Tebow left, it’s all garbage now. When was the last time they won a national championship? When Tebow was there. Since Tebow left, no national championship.”

“No!” Adrienne said. “Don’t even talk to me right now.”

The friendly ribbing was a playful, fun interaction among friends, in the same way you might give your friend hell for cheering on a Dallas Cowboys team that hasn’t won anything of importance since the 1995 Super Bowl.

Back to our conversation, it wasn’t until Nik and Bob spoke candidly about their wives’ pregnancies that the gravity of what I was watching grabbed hold.

“Everyone’s telling you that you might as well start preparing for lifelong care,” Bob said.

“That’s what we experienced,” Nik said.

“From day one?” I asked.

“That was literally from pregnancy. We went to have an ultrasound, and they go in there and they measure their markers. It identifies and shows you if they’re at risk — and then you hear all this stuff. They come back and say, ‘Well, you know, Adrienne has some markers for Down syndrome. So we want to—”

“Let’s just stick a big needle inside to test,” Nik said.

“And here’s the 4,000 pages you’ve got to sign so you don’t hold us responsible.”

“In case we kill them or damage them.”

“We don’t need all that,” Bob said matter-of-factly. “And then they ask, ‘Well, don’t you want to know?’ What do you mean? Why? What are we gonna do if she does or doesn’t? And they ask, ‘Are you willing to handle a child like that?’ Well, how do you know you’re equipped to handle a regular child? Nobody is ready when their child comes. But you learn.”

I felt a pang in my stomach thinking of my own two daughters and what I would do — how I would feel — if a doctor had told my wife and I that either of our kids would need lifelong care and would amount to nothing.

Thinking on those diagnoses today, I wonder if it was a sign of the times. As a society, we’ve learned so much about the neurodivergent community that wasn’t readily known 20 years ago. Doctors, it could be argued, didn’t have the research, knowledge or understanding that’s available today. Twenty years ago, there weren’t athletes like Adrienne making national headlines by breaking the mold that society tried to cast them in and who, instead, carved their own path.

Yet for all the strides that have been made, it at times can still feel like an uphill battle for these families. Take a speech Robert F. Kennedy Jr. gave in mid-April. The secretary for the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services said at a news conference that the growing rate of autism in the United States is an “epidemic” that is “catastrophic for our country.”

In saying “autism destroys families,” Kennedy added, “These are kids who will never pay taxes. They’ll never hold a job. They’ll never play baseball. They’ll never write a poem. They’ll never go on a date. Many of them will never use a toilet unassisted.”

June Bunn listened to the speech a day before our interview and was still irate at what she heard. Her otherwise soft and easy voice quickened and grew more intense with a fierceness in her words. She said while she otherwise supports Kennedy’s efforts, like keeping foods clean and removing red dye, she couldn’t believe the stark language in which he spoke.

“What in the world are you thinking?” she said. “We feel like you make such great gains and then — like is that not enough of a betrayal of what can be done and what is possible with these kids? Have you ever met a child with autism?” She paused for a moment, catching her words. “We shut that out and try to just —”

“Since day one, we’ve tried to shut it out and say, ‘We’re not listening to that. Treat them like everybody else. Everybody’s got potential.’ April is Autism Awareness Month, and his speech was very dark, very gloomy. It’s the opposite of everything that we want to portray about these kids.”

As she spoke, I thought back to my conversation with Nik and Bob at the breakfast bar. I asked them both how they felt as parents hearing those words from their doctors: Lifelong care. Are you ready as parents? Did they want to explore other options?

“It’s heartbreaking,” Nik said.

“I remember thinking it’s not gonna matter,” Bob said. “Because for us, as long as she’s born a healthy child, that’s really all we want.”

“And look at them now,” Nik said, “they’re running marathons, triathlons. They’re living life. They’re enjoying their friends.”

Sure enough, the next day Adrienne set a personal record, running the half marathon in 1 hour, 48 minutes.

Adrienne joined Chris in Kona when he completed the race in 2022 — two years after finishing his first. She found the atmosphere electric. At that point, she had never completed more than a sprint triathlon, but she began to wonder: Could she complete an Ironman?

Back home in Ocala, Florida, she began working with a unified partner, Doug Guthrie, who would guide her through her six-month training plan and on race day through Hawaii’s heat, hills, and humidity. That meant swimming at 4 in the morning before school, then a full day of school, and more training in the evening.

Because Florida is fairly flat, she drove to Clermont, an hour north, to bike through the hills. Adrienne knew how to ride a regular bike, but had to learn a road bike and how to clip in and shift gears — all while dealing with the sensory overload that came with the wind, passing cars or screaming ambulances.

In all, she was training upwards of 25 hours per week. One of Adrienne’s strengths, though, is her focus.

“Whether it’s training for an Ironman, studying for college, or working toward a goal, my ability to hyperfocus helps me push through challenges,” she wrote on Instagram for Autism Awareness Month.

Training didn’t come without its challenges.

Some mornings were met with tears, a sign for mom and dad to call Doug for a day off. Some days they watched Adrienne’s overstimulation and sensory overload settle in, as Adrienne would repeatedly clinch and release her fist, getting out little fidgets. Adrienne would put on her headphones and retreat to coloring, lining up each individual color and using them one by one. Other times she practiced diamond art, where she placed teeny-tiny colorful beads on paper, one by one, to create a beautifully detailed picture.

“It allows her to go into her own world and put her world back in order,” June says.

There was also the fact Adrienne was still 17 and Ironman rules dictate that athletes must be at least 18 to race. Adrienne had a sponsor lined up to help fund her race and gear, but the company wanted to know that she was healthy and could manage the 140.6 grueling miles. So two days after her 18th birthday, Adrienne competed in a Half Ironman (70.3 miles), proving not only was she capable, but she had the determination to get it done. It’s a testament to her autism: when she sets her mind to something, she sees it all the way through.

Finally, it all paid off on October 14, 2023, when Adrienne crossed the finish line with her beaming smile, happy stomps and bear hugs with her family.

“I loved competing in Kona,” Adrienne says today. “I’m very proud of myself to do that.”

Her parents celebrated just as well, though June admits she couldn’t help but feel some PTSD from the flashbacks of her pregnancy and Adrienne’s diagnosis.

“It definitely takes you back,” June says. “Sitting there for the diagnosis, wondering what it’s gonna look like, what her life is gonna look like, how it’s gonna —

“And then you’re standing in Kona and you’re just like, ‘Oh my God, she did it! It’s overwhelming. And to see her continue to grow is …”

Bob chimes in: “Everybody has something to offer — no matter how big or small. Everybody that said, you know, ‘She’s never gonna drive. She’s never gonna finish school. She’s never gonna do this. She’s never gonna do that’ — yada, yada, yada. And to that, I say, ‘Look, you should never say never. Everybody has a niche or a lane …’”

“A path,” June says.

“Right. And Adrienne found her lane. And, you know, lo and behold, she’s able to touch and inspire other people that are trying to find their lane as well. Maybe it’s not running. Maybe it’s not athletics. But there is a lane for everybody. Don’t stop looking for yours.”