Breezy Johnson has some strong feelings about this particular time of year.

“Well, I do hate spring, so there is that. It is my least favorite season, because it's too muddy to do anything down in the valleys, but it's not snowy enough to do snowy things in the mountains.”

The 29-year-old speed specialist for the U.S. Ski Team may not appreciate the season of regeneration, but after the World Cup campaign she just completed, who’s to argue with her if she wanted a longer winter?

When the calendar turned to a new year — 2025 — it was almost as if her speed events saw a rejuvenation of confidence, where the promise she has displayed over the past 11 years finally manifested itself in a torrid cluster of race results.

In St. Anton, Austria, she finished 16th in training and 11th on race day.

In Cortina d’Ampezzo, Italy, her two training runs were good for 4th and 15th; race day she finished 22nd. This course, site of the 2026 Olympics, holds special meaning for her. It’s the site of a horrific crash in 2022.

The White Circus moved next to Germany, where she crushed her training runs at Garmisch-Partenkirchen, taking 7th and 2nd. On race day she finished 4th.

And then, the first week of February at World Championships in Saalbach, Austria, all that confidence filled her cup and spilled over. Breezy’s training run was good for 6th. On race day, she became a World Champion, taking the gold medal.

Three days later, she’d combine with the other-worldly Mikaela Shiffrin — she of the most World Cup wins all-time — to win gold in the Team Combined.

And because momentum is a beautiful thing, she wasn’t done.

At the European Cup in Sarntal, Italy, she took 1st and 3rd in Super G. And then at the famed Kvitfjell track in Norway, training runs of 11th and 1st led to finishes of 3rd and 10th.

There was a time when it was always supposed to be like this. That was the expectation, anyway. Her journey since 2014 has seen plenty of success, a few too many injuries and an all-too-avoidable suspension.

At a recent U.S. Ski Team fundraiser, a common theme among current and past racers bubbled to the surface.

“There were a bunch of former ski racers there who had various levels of success, and a few of them talked about how there was always so much hope and it just never totally worked out the way that they wanted it to.

“They were talking to a bunch of donors that had helped them in their ski career. And I think the thing that's been really meaningful to me is being able to get some level of a happy ending for the people who have helped me.”

If momentum is a beautiful thing, then hope speaks to something magical. For all she has endured, hope and momentum may carry her into an Olympic year with the chance to do something special, and dull the pain of dashed dreams.

Born Brianna Johnson, the Victor, Idaho, native legally changed her name to Breezy in high school with the help of her parents. Breezy is a nickname she’s always embraced, and even today adds a hashtag for social channels that celebrates her unique moniker: #likethewind.

She learned to ski on the gentle slope of her family’s driveway thanks to her patient father. The Johnsons live on the western slope of Teton Pass, on the Wyoming-Idaho border, minutes from Jackson Hole and Grand Targhee ski resorts.

“My dad taught us to ski. We have a little incline and he’d just drag us up and we’d ski down.”

Although she entered the U.S. Ski Team orbit around the age of 18, she never thought the venerable program was counting on her as a contender.

“I always felt like there were a lot of people that thought I wasn’t doing anything. I wasn’t what they were looking for, like who they thought would be a future Olympian or win an Olympic medal.”

Breezy had her own plan. Two years later — in 2016 — she earned her first World Cup points. The following season she secured a spot on the World Cup team, finishing in the top 25 in the world in downhill. She was the youngest person to qualify for the downhill World Cup Final since legendary Swiss skier Lara Gut had achieved it in 2008 at the age of 16.

“That was kind of when I feel like people started taking me seriously,” Breezy says. “Then it was a pretty fast trajectory.”

Pyeongchang, South Korea, hosted the 2018 Olympic Winter Games and the upstart from Idaho was on the team, and feeling like she could make some noise. In the event prior to Pyeongchang — at Garmisch-Partenkirchen — she sandwiched 4th and 7th place downhill finishes around a 1st place training run.

“You know, I felt like I was a medal potential. Not a favorite, but that I definitely had a shot at getting a medal at the Pyeongchang Games. And that was also a pretty big turning point as well for me because I went to those Games and everybody had kind of been like, ‘Your time will come, your time will come.’

“I went there and I was like, ‘I want to do this.’ I need to figure out how to make my best as good as the best out here.” She finished 7th at the Olympics, part of a strong American showing with Lindsey Vonn taking bronze and Alice McKennis scoring a 5th place showing.

As the offseason began, Breezy says she “went to work.” She was excited by her potential, there had been some coaching changes within the team, and when one of the early camps arrived in Chile, she felt ready. What came next, though, would derail the best laid plans.

She blew her knee in training, “which was really brutal mentally. And then, I had to watch that World Cup season, which was the first time I had to kind of watch the World Cup tour since I joined.

“I was watching people win races, and I was like, ‘I can fucking do that.’ But, you know, I wasn't there.”

Ski racing can be the cruelest of sports. It can be joyous and isolating in the same day. It can feel euphoric and emotionally crushing. The support of an entire team of athletes, coaches and trainers will have your back, but the distance of rehabbing an injury can be downright lonely.

And then there’s the cold reality that having one injury doesn’t mean it’s the last injury. The toll it takes on the body — the knees, the tibia and fibula, the hamstrings and the hips, the head, physically and mentally.

To say it’s a grind doesn't do it justice.

Which Breezy immediately felt upon her return.

“Yeah, then I came back, I was skiing really well that spring, and injured my other knee. I was really close to full dislocation of my knee, which would have been really gnarly.

“I tore my whole joint capsule. So it was definitely the grossest. I remember driving back to fly home and I was sitting across the seat in the back, and when (the driver) hit the brakes, my whole knee would just collapse.”

The two injuries — on opposite knees — would sideline her for a year and a half. But she wasn’t done. Not even close.

“I'm a big race horse. I really like racing.”

While the Covid-19 pandemic messed with the world, ski racing continued with certain adjustments to schedules and protocols.

In November of 2020, Breezy put together a ridiculous run of results, beginning with two national championship podiums at Copper Mountain, Colorado.

Next were two bronze medals at Val d’Isere, France. A bronze in St. Anton, Austria. Another bronze in Crans Montana, Switzerland.

She carried the momentum into the following season, taking two silver medals at Lake Louise, Canada. Another silver came at Val d’Isere.

And this is where Cortina d’Ampezzo re-enters the story. It was January of 2022. The Beijing Olympics were a month away, and Breezy arrived in Italy with confidence.

“I did the first training run and felt good. Second training run, I went off the Duca jump, it's probably the most hated jump on tour. Because you're going really fast and it's a really flat landing. So I went off of that, realized almost immediately that I was going really high … I was just, like, massively high off the ground.

“Landed immediately. Felt what turned out to be my cartilage and meniscus, like, cracking and falling apart … and so I crashed again.”

She had been here before. Too recently. The mental toll of getting injured in a sport like ski racing is more than missing out on the medals and the world travel. When you’re healthy, almost all of your expenses are covered. The top skiers earn a very good living. But when you’re injured, Breezy explains “there’s not a good safety net.” The team provides medical insurance, but the athlete pays the deductibles. And when you’re not racing, you’re not making money.

Pile on a pressure most wouldn’t understand. The Olympics are every four years. Spots are limited. Luck and fortune have seats at the table. In Breezy’s case, she was skiing so well. She tried to find a way.

“I no longer totally felt able to ski at the Olympics, but I thought I might be able to figure it out. We talked with the doctors and I decided that I couldn't and shouldn't do it. And so, I went home, I had surgery, and woke up to all of my friends' pictures at the Opening Ceremony.”

Already feeling “unmoored” by the string of injuries, Breezy had yet another obstacle to overcome. Athletes on the biggest stages are subject to random drug testing, even during the offseason. Part of the pledge from the athlete is that they will make their whereabouts known to entities like the United States Anti-Doping Agency or the World Anti-Doping Agency.

Hypothetically, if the athlete is vacationing in Thailand in June, USADA knows where to find and test you.

Breezy accumulated three “Whereabouts Failures” in a year and was suspended for 14 months by USADA. The suspension was enacted from October 2023 until December 2024. There’s an important distinction to make: Breezy did not test positive for illegal substances.

She told The Washington Post she had become “complacent” in her approach to notifying the agency on her whereabouts. For her final strike, a USADA rep reached her at the family home in Idaho. A despondent Breezy was convinced she had provided that address. USADA told her they had something else.

As crushing as it was, she took ownership of her situation. She trained in isolation, determined to return a better skier and a more focused athlete.

“That piece was tough, because your reputation is important to you as an athlete. You don’t want to be accused of being a cheater,” she says.

The peaks and valleys, the wins and losses, the injuries and the suspension. They all accumulate to form both an identity and a foundation of knowledge. She has become known for her work off the piste, advocating for athletes in a sport where you are often forced to go alone when the team says “no.”

Becoming a leader wasn’t something she sought. Portions of her work have been with USADA, searching for ways to modernize the system that tracks athlete movements.

“Leadership is not necessarily given to the person who seeks it out, but the person who is the last one standing in the room when they're looking for feedback. That was kind of how it felt to me. I experienced some tough things early on in my career and I realized at one point that not stepping up, not talking about it, just hoping that somebody would come save me just wasn't going to happen. And if I needed change, if we needed change, then somebody was going to have to do that. And I talked about that with people.

“And then they were like, ‘Okay, yeah, you should go talk to them about that.’ And then I was like, 'Well, I didn't really mean me, but okay.’ In some ways I was lucky because I've had a pretty successful career. I have never really been on the chopping block.

“Growing up, I was often considered to be not a good team player. I just needed some growing and to figure out what things I needed to be a leader about before I could do that. And so that was where that came from.”

Breezy credits her parents for instilling a strong meter of what’s right and wrong. Sometimes that upset others, because she wasn’t afraid to use her voice.

“When people get upset sometimes, I always make the joke that ‘I'll outlive you because I've been in this sport for a long time, and I've seen a lot of people who were very frustrated by what I advocated for and what I said.’ And I'm still in the sport, and they're not, and so I'm a little bit hard to get rid of, I guess.”

Add it up. She’s been sidelined for more than two-and-a-half years of her prime. At first, the injuries. Then the suspension.

Returning for the ’24–’25 season healthy, hungry and focused, she parlayed her talent — really the accumulation of her personal skiing history — into two gold medals at World Championships in Saalbach, Austria.

She finished top three 10 times when you account for training and race day. Twelve times she was top five. Fifteen times she was top 10.

It speaks to her talent, of course. Consistency is a necessary ingredient of confidence.

And now she’s looking at potential bookends of Hollywood proportions.

Cortina. Site of her crushing injury in 2022.

And site of the 2026 Olympics.

“When I left Cortina in 2022 I didn’t know how I was going to come back in four years. That wasn’t a question I could answer then. Now, I can say that I do feel good and confident I can do it going back to Cortina.

“There’s still a lot of work to be done. And I'm not saying that it'll be easier, I have this in the bag at all, but to feel like you're capable of writing the end of that story is kind of all we as athletes ask, you know? And that’s very exciting for me.”

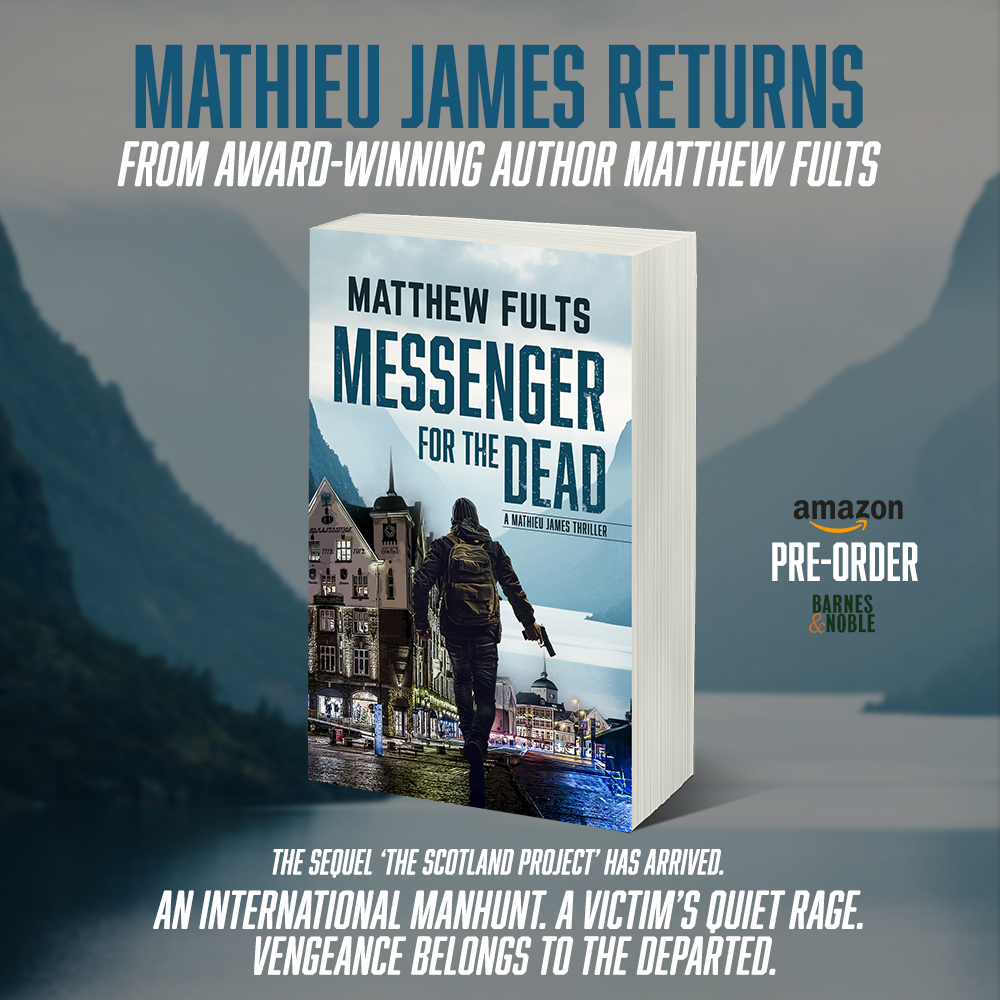

Matthew Fults is author of the award-winning novel, The Scotland Project, available from your favorite bookseller. Its sequel, Messenger for the Dead, is available for pre-order.