When Kelly Curtis was in the third grade, she took up wrestling. Mind you, there were no girls’ wrestling programs in New Jersey for the aspiring elementary school grappler set. So she took to the mat with an eye on showing up the boys. And she didn’t disappoint.

“I was pretty good,” the 36-year-old Curtis recalls. “I was pinning boys and making them cry and I had a great time.”

She so enjoyed the competition that she did what most girls her age would do: she invited her best friend to join her escapades.

“She was a ballerina and just completely out of her element,” she laughs, adding, “It was a great time.”

While wrestling didn’t stick long term, the youngest daughter of former NFL player John Curtis and his wife, Debbie, did discover her element in two sports. The first, which became her true love, was basketball. And the second, which changed the course of her life, was track and field.

Nearly three decades later, those bawling boys pinned by the girl with the competitive spirit can look her up and discover she’s grown into a bit of a badass: Winner of the prestigious Penn Relays in heptathlon, bobsled athlete-turned-skeleton slider, active-duty U.S. Air Force senior airman and … Olympian.

Lest they still suffer from humiliation, of course.

When Kelly was young, her father would take her to the Penn Relays, the country’s oldest and most competitive track and field event hosted by the University of Pennsylvania. She later learned this was something of a family tradition.

So when she won the heptathlon competition at the 2011 edition, it had special meaning. Not only had she left Division I Tulane University to attend Division III Springfield College, she was competing collegiately in a sport that opened doors she never expected.

Kelly's journey to skeleton has been quite the ride, and she's all-in for one more Olympic Games. [Courtesy photo; AP photo]

“Oh, man,” she says, recalling the glory days. “It's such a fond memory. It was like everything came together at the same time, which is so rare in a heptathlon. I didn't win a single event, but I did well enough, you know, picking up a second and picking up a third. I did well enough points-wise where when it came down to the 800, the last event, which is historically my worst event, that was it.

“I held on enough for the win. And it was a little emotional for me as well, because I knew that my grandfather brought my father there when he was a kid, and then it's just been such a blessing to be part of something like that because it meant so much to my family. So, yeah, it's just something that I'll always look fondly upon.”

Taking the top podium at that event filled something of a void — at least until recently. Kelly had dreamed of winning a national championship in college. That dream didn’t materialize. But she managed to find a way nonetheless, even if a decade or so had passed since she graduated.

“That was probably the pinnacle,” she says of the Penn Relays. “I mean, I was a Division III athlete at the time, and it was against Division I athletes, which is always cool. But I always wanted to win a national championship, and I'd never won one. I never won one in college. My first one was a couple months ago.

“Winning the skeleton national championship, for whatever reason, I hadn't participated in the skeleton (national championships). And then this past one was also our team trials. So it was my first opportunity to put myself out there and end up winning a national championship, which I'm just like, ‘Oh, wow, I finally got one.’”

John and Debbie Curtis raised four children — two of each — in a family that didn’t lack motivation for achievement. John was drafted into the NFL in 1971 by the New York Jets. The record-setting receiver for tiny Springfield College — yes, one and the same — was taken 214th overall long before he started a family.

Little did his future children know he was setting the benchmark. He would continue his NFL career playing for Kansas City, the Baltimore Colts, San Francisco 49ers and New England Patriots.

In a 1971 article in the New York Times, Curtis was one of many rookies interviewed for a story featuring the Jets’ draft picks.

“I think about it after a poor practice,” Curtis said. “If you drop a ball, you wonder if that's it. In college, you knew you had a nine‐ game season. Here it's a day to‐day existence. The encouraging part is that I've had a few days of good practices, I've made some nice catches.”

The other day, Curtis jumped offside, wasting a play in the offensive drill.

“That's the first time that's happened,” he said. “I hope it's not a big minus.”

An innocent comment about making the most of what you’re given — living day to day — would turn prescient in his future daughter’s athletic journey.

For most of her life Kelly was chasing her older brothers, who wrestled and played football, basketball and baseball. Brother Jay followed in their father’s footsteps and played at Springfield College.

“I was just trying to keep up with them. And I think being the baby built a good base for me because I was able to see what athletics my siblings excelled in and which ones they didn't really enjoy.

“My mom had to drag me from practice to practice and game to game. And when my brothers are playing baseball, I'm just like climbing the sand pits or trying to do whatever on my own. I think that freedom really allowed me to build my base with athleticism.”

Kelly saw herself playing college basketball. But when track and field started presenting the better alternatives, she seized the moment, first signing with Tulane before transferring. Her ability to roll with it — to live in the moment and make the best of her situation — turned her life inside out.

“I was at Springfield College. I was doing the heptathlon, and I had this conditioning coach tell me that I might be able to be a bobsledder post collegiately if I wanted to go down that avenue. So it was always like on the back burner. I never really thought people actually did that until I saw Erin Pac, who won an Olympic bronze medal in the 2010 Vancouver Games.

“She was a Springfield alum. She did the heptathlon and she transferred those skills into being a bobsled pilot. So she set the example … They can make a career out of it. They can follow their Olympic dreams in a sport that they didn't grow up doing. And she had that Springfield connection. So I reached out to her and she gave me the lowdown of what to expect.”

During our conversation, Kelly twice apologized for the roaring background noise that was U.S. Air Force fighter jets.

“The sound of freedom,” she quipped as she sat outside under a bright blue sky at Aviano Air Base in Italy. She lives there now with her husband, Jeffrey Milliron, and young daughter, Maeve.

How they arrived there is a story in itself.

After getting that lowdown from Erin Pac, Kelly attended a tryout for the U.S. Bobsled team. In that moment, she was like a thousand other athletes who have graduated college: looking to satiate the competitive appetite.

After Springfield College, she enrolled at St. Lawrence University in Canton, New York, where she pursued a master’s in educational leadership with the idea of following her in father’s footsteps and becoming an athletic director. She was also coaching with the St. Lawrence track and field team.

“I was coaching and I still felt like I had something to give, competitively,” she says. “And a lot of my classmates were getting into marathon training. And I was like, ‘I don't want to be a distance runner.’ And then there's also the CrossFit movement and I tried that and I didn't really like it.

“Then this combine for bobsled and skeleton was there and it was testing explosiveness and strength. And coming from the heptathlon, I'm like, ‘Yeah, this is something that I could train for.’ And then I did my first combine, just wanting to get a baseline of it. I did well enough in that combine that they invited me back.”

During the 2014–15 season, around the age of 25, she found herself in the organization’s developmental program as a pilot, learning to drive the bullet-shaped rocket-on-skis down the icy tracks in North America. On the side, she was experimenting with skeleton. She found the idea of speeding headfirst down the track at 80 mph exhilarating, and switched to skeleton full time. In 2017–18 and 2018–19 she earned North American Cup championships, a level that provides a path for athletes to earn World Cup berths.

Which she did, earning her first World Cup start in Königssee, Germany, in January 2021, placing 19th. Her next start would come 10 months later in Innsbruck, Austria, where she finished 9th.

Early in her pursuit of a new sport, Kelly was like most aspiring Olympians. She took odd jobs to pay the bills. Among those, she was a dog walker and appeared in a background role as a vampire for the AMC show “Preacher” — “probably the most proud my mom has been of me,” she laughs.

Seeking professional and financial stability, she began researching the U.S. military’s World Class Athlete Program.

“I thought I was going to go into the Army one. And then my teammate Katie Uhlaender, after I had already been in touch with the recruiter, was like, ‘The Air Force is going to start recruiting civilians similar to how the Army does.’"

Nearly five years ago, Kelly joined the U.S. Air Force, following in the footsteps of her brother, Jimmy. She was the first winter-sport athlete enlisted into the Air Force’s World Class Athlete Program, and when not training works in records management.

In a mishmash of whirling events, she finished boot camp, was able to choose her station — she and Jeffrey picked Aviano due to its proximity to Cortina, site of the 2026 Olympics — and moved onto base just 10 days prior to the Beijing Olympics, for which she had just qualified on the last run of her last event.

“I had very low expectations to actually make the Olympic team. Then it came down to the final race, and I was behind my teammate with an attainable amount of points, but still low expectations because she had been to the track prior, I had not.

“She just had the experience and I was like, ‘I'm probably going to go back to work on a military base next week. So let me just make the most of it.’ And it turned out to be my best performance of the season. I had two massive personal records in terms of competition, and I placed sixth.

“That was my highest finish of the entire season. I ended up overtaking her with the points. And then, I'm next to the leader's box and I'm seeing myself move up the ranks and I'm like, ‘Oh my God, I think I made the Olympic team.’ So that was a big surprise.”

She finished 21st in Beijing, but she also made history. Kelly was the first Black athlete to compete for the U.S. in skeleton.

“It's a source of pride and it's cool that I've come from such a strong lineage,” she says. “My grandfather's grandfather was enslaved. So to think that their descendants would do something like what I'm doing right now, you know, they couldn't fathom it. Neither could my mother's side.

“It's so incredible. I'm proud to be of all the different cultures. I'm proud to be coming from a place like America where my story could be told.”

But her story isn’t quite done. She took a year off from competing to give birth to Maeve, and returned for 2024–25 with the goal of earning another crack at the Olympics in 2026. It didn’t come without doubts, though. “It’s been done before,” she says, referring to two bobsled teammates who are also mothers. “But when you’re in it, you’re just like, ‘Can I get back there? Can I do it? Do I want to do it?’”

Things turned out pretty well. Kelly finished the season with a 10th-place finish at World Championships (along with that national championship she always dreamed about).

This is version 2.0 of Kelly Curtis. She’s now a mom competing on tour. Her body has changed, her mindset is different, she travels with husband and baby as her personal entourage.

“The mental aspect of it has been the most challenging so far. But now that Maeve is 18 months, I'm like, ‘Man, I'm really glad I stuck with it because I feel like that fire’s back. Everything's been leading up to Cortina. Everything's back fully functioning. My push is the best I've done, but I feel like I have the potential to do more, so I'm excited to see where that will be this upcoming season as well.”

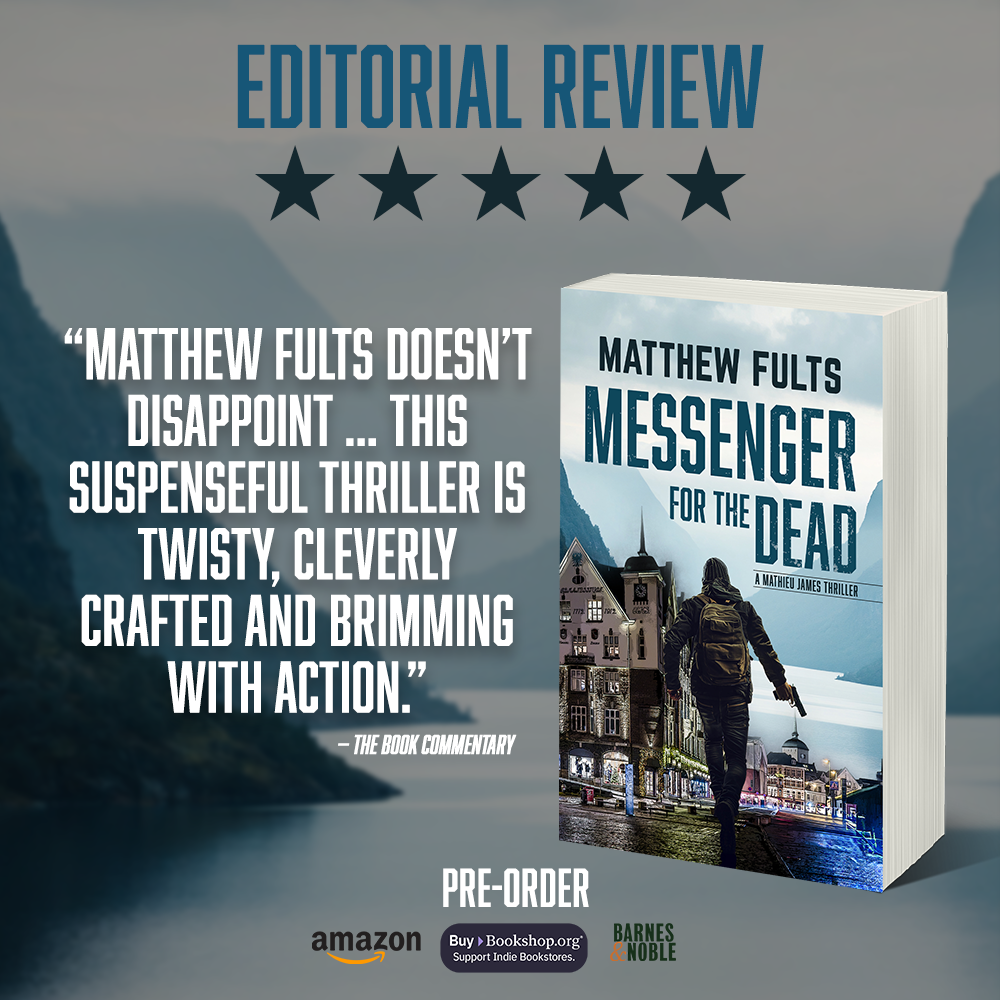

Matthew Fults is author of the award-winning novel, The Scotland Project, available from your favorite bookseller. Its sequel, Messenger for the Dead, is available for pre-order.