This story starts with a curious young boy working the family farm in the flatlands of Belgium.

This young boy, Tom de Dorlodot, found his adventure seed when, with the help of an acquaintance, he discovered a dilapidated glider one weekend while home from boarding school.

And well, who doesn’t love an old glider to mess around with? Curiosity bested whatever practical senses the teen may have possessed.

“We took it to the soccer field and started to play in the wind with it. I thought, ‘Oh, this looks cool. This is something I would like to do.’ I really remember the one moment that changed everything,” Tom says.

“We start playing on a hill. And I kind of took off just for just a few meters. Then I thought, ‘Well, here I am flying.’ It was really a beautiful moment. And from there on, I started to put some energy into that.”

That adventure seed was now planted near the family farm. Tom would grow in tandem with this seed. The two latched on to one another so tight that eventually, they’d nearly squeeze themselves extinct more than once.

Small hills led to bigger challenges, one after the other, as his confidence grew and the only thing keeping him from more aggressive pursuits was his imagination.

As it turned out, his mind had no limits for his body.

In between then and now, Tom has paraglided across Africa. He was the first to fly a glider over Machu Picchu. He set the distance record for flight when he piloted from Brussels to Istanbul. The list goes on and on.

That’s not to say his thirst for the extremes hasn’t come without cost.

He’s also broken his back, severed his finger and suffered a training accident that was so violent, he nearly lost his leg and has been in a wheelchair for almost a year.

Pt. 1 - Flight of the bumble bees

Earlier this year, Tom and I navigated several changes to his schedule, namely one that involved yet another surgery on his damaged leg. We stayed in touch via WhatsApp as he navigated Europe, certain we’d connect when he had time.

About two weeks before we finally caught up with each other, he sent me a photo and a video. Both depicted a hive of bees. He wrote, “Working on a swarm here.” I didn’t understand the context.

So when we finally connected, I asked him about the bee missives. It turns out, the adventure athlete likes making honey. And the bees are learning from their keeper. They saw a chance for their own adventure.

“They tried to escape with the old queen and stuff. So I had to take care of that. For me, really, at the end of the day, anything that connects me to nature, it's good. I could be sailing, mountaineering, climbing, flying, free diving or beekeeping — it all goes together.”

And now it’s all starting to make a little more sense.

Pt. 2 - The farmer’s son plants a seed

Those weekends home from boarding school, when he would experiment with the old glider, became a little stale. He craved something more. So he took the glider back to school with him, bent on executing something more technical.

“I think I've always had this kind of spirit in me, you know, of trying to push the boundaries and see what was behind the next hill and things like that. So when I was 16 years old, I took it to my boarding school, and it was a really cool place to live in nature.

“There was an abbey where a monk lives. So I flew in between the two towers — it looked like a church. Basically, I just flew in between. I was trying to play around and already kind of pushing the boundaries and technically, I was not really good yet, so it was a bit sketchy, but that's how I started it.”

That seed planted at home and nurtured at boarding school started to mature when he went to university. Tom was studying journalism, a career that would become very relevant to his future life. But he couldn’t shake what was growing inside him, which by now had sprouted into a full-blown adventure-seeking, death-defying weed.

It grew and wrapped itself around his core, and eventually his heart. And now, at age 20, he was flying from Brussels to Istanbul. This trip, one of the longest recorded, was when his future revealed itself.

Pt. 3 - The golden road

“My mum used to ask me, ‘Hey, Tom, do you really think you're going to make a living out of air?’ It’s a pretty cool way to put it,” he says.

It turned out, he was. That zany idea to fly from Brussels to Istanbul opened his eyes to the how — how he could make it financially feasible chasing one adventure to the next.

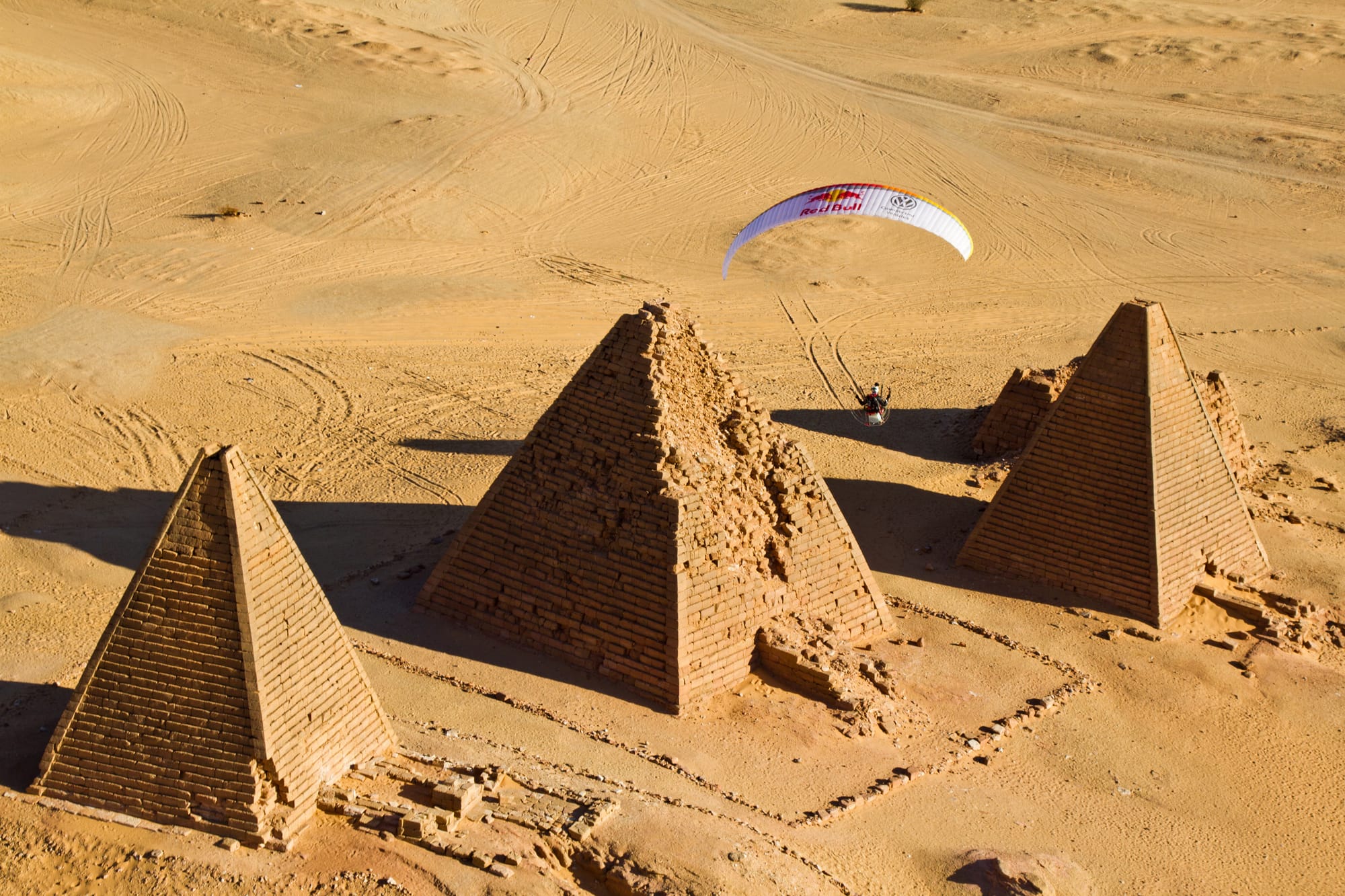

“You know, the first time I really did something big I realized that the newspaper seemed to like it. It was before YouTube and all that. I thought, ‘Maybe if I tell a good story, maybe I can get some support.’ And so very early on, when I was 22 years old, I would start getting sponsored by paragliding brands, and then Red Bull and Volkswagen and things like that.”

Thus began a quest of seeking one adventure to the next.

Tom discovered that making content centered on his adventures could be a good way to make a living. [Courtesy photos]

“Slowly but surely, I started to make a name for myself. And I was competing and I was trying to break records and flying long distances and at the same time I was studying, so I was at university studying communication and I was studying to become a journalist. I was really into that, and then I did a masters in movie directing and photography, and so that really helped me.”

Tom could see the path. His vision, with each passing day, was clearer and clearer. If he could make compelling content built around his adventures, this could be a pretty great life. He started making commercials for Volkswagen, piloting a camera over pristine remote territories, highlighting the capabilities of the vehicles. This was before drones, and when helicopters were the primary (and costly) means of capturing aerial footage.

Down the road, Red Bull would become a sponsor, giving him access to their proven athlete-success formula. Succeeding at one job after another, he was laying the foundation brick by brick. He was learning content is king. This is how I make it work.

Yet his family still wasn’t convinced.

“They were challenging me a little bit,” he says. “I remember going to see my grandfather even when it was really going great. We were doing amazing trips and pretty decent budgets and stuff. My grandfather would look at me and say, ‘Tom, when are you going to get a real job?’

“And I was like, ‘This is a real job. This is working.’”

He calmly stated his case, suggesting he was doing better than his brothers — one a lawyer and the other a major event producer — and his cousins.

“I was lucky that they were concerned and they were asking me, but they always supported me. ‘You know, whatever happens, you can always come back here and we can sort that out.’ And so that kind of gave me the confidence that I had a really good base.”

Pt. 4 - You can’t outrun fate

For all the amazing sailing trips, all the peaks he has soared above and all the records he has broken, there was always a price to pay.

The broken back.

The broken foot.

The severed finger.

Those three injuries happened in consecutive years. He recounted this on a video call from his home in the Azores. In the background, power tools were piercing the audio space, cranking this and tightening that, and he needed to escape the racket and find some peace. He asked for a moment while he changed locations in the house.

This was when I learned he’s been in a wheelchair for the past year, thanks to his most recent accident. He rolled through different rooms, heading for a quieter place while we made idle chatter. I knew he had a badly broken leg, and that the number of surgeries were piling high. But this — the wheelchair — was a little jarring.

Tom is rugged, trim and kissed by the sun. He looks the part of adventurer. He is joyous to speak with … as engaging an athlete I’ve ever encountered. On his Instagram, he shares photos of his young family. Wife Sophia, and their kids Jack, 6, and Leonor, 4. His son Jack sailed across the Atlantic shortly after he was born, albeit as a passenger. But who else can claim such a thing? The indoctrination to the family business came early.

Given his current physical state coupled with two young children, I posed the same question I’ve asked other adventurists. How do you weigh the risk/reward?

Earlier in our conversation, he shared a couple of his quiet mental conversations — more bullet points than essays.

Disaster is looming. Shift before you have to.

Transition has been on his mind. He’ll turn 40 soon. Still so young, but old enough to absorb the wisdom of his experiences, and listen to the voices inside his head.

“You realize that when you don't have kids, it's your problem. You have an accident, you're alone. This you can deal with it. But if you have kids, then all of a sudden it's your family's problem, you know, and everyone is involved and it impacts everyone. So now there's one thing I know for sure: I don't want to get hurt anymore.”

Pt. 5 - What happened in Norway

Early in our conversation, I asked Tom a hypothetical question: If he was sitting in an airport and a stranger asked him what he did for a living, how would he answer?

“Well, I usually say that I'm a professional paraglider pilot. I'm an adventurer. This is where I would go. Every time I say that I'm a professional paragliding pilot, people think I'm an instructor or something like that. But, no, actually, I'm really going on adventures and getting support from the sponsors to make that happen. And, I'm also a storyteller, so, the plan is always to come back with a good story and maybe a documentary or good images.”

Surely that’s the simple sell; the elevator pitch. He’s so much more, especially when it comes to his adventures. It’s not just paragliders. He’s sailing oceans, he’s kite skiing and jumping out of airplanes. Adventurer is a neat, tight word to relay so much. But it undersells the truth.

Which brings us to Norway, and the accident that upended his life. He was there training for a kiting expedition when his good intentions left things in disarray.

In his words:

So that was a bit of a stupid accident. Like every accident. But this one I have a bittersweet taste because, basically, I was preparing to cross Greenland on a big expedition.

It was a Red Bull project. It was a long distance and everything was ready. But then I thought, ‘Okay, I want to do this seriously.’ So I'm going to Norway and train for three weeks with some of the best instructors. And so I went to a school there, and I had an amazing instructor for a week.

I've been coaching for years, so kiting I know, but all the things that you need to know in the very cold situation — really cold — I had a bit less experience. I've been mountaineering for years and stuff, but that one I just have to do it well and properly. And so I was training with that teacher for a week.

And then one day she said, ‘Hey, Tom, I'm not available tomorrow, but a friend of mine's going to guide you through the mountains. You're going to go and train with him.’ And that very day, the wind was extremely strong. And I'm a sailor. I'm a paraglider pilot. I know about wind.

I said, ‘Well, this seems to be really windy.’ And I told the guy and he said, ‘Yeah, yeah, but you have to train. If you come to Greenland, you're going to have these kind of conditions and stuff.’ And I thought, 'Well, I'm in a safe environment. I'm learning with an instructor. Just do what he says and that's it.’

And, at one moment, we packed everything because the wind was really strong. And basically, he was next to me, helping me with the kite. But for whatever reason, I got ejected. Like, I flew off. I went maybe five, ten meters high and crashed, but it was a massive, like a really, really violent crash and I broke my leg. And then I got dragged for like 100 meters, full speed, bumping into the snow, ice … I broke my helmet.

And when I stopped, I finally dropped the kite and my leg was broken.

Tom’s intuition told him to cease earlier that day. He knew the wind was too strong. It’s a mistake he regrets — not listening to his inner voice. He put himself in a dangerous position. He paid a price. But on that day, he didn’t know how steep the tariff was for such neglect.

The break itself wasn’t bad. He was flown to a hospital in Norway, where he stayed for a few days without much attention from the staff. Doctors finally put a fixator on his leg — a Frankenstein-looking, Hannibal Lecter-inspired device to stabilize his leg. It’s basically drilling metal splints into the bones and attaching them to a halo around the leg to keep it steady.

The danger is inherent. Tom's future depends on his recovery, and his willingness to accept risk. [Courtesy photos]

But they didn’t give him antibiotics after the procedure, and his leg became severely infected. This is when the cycle of surgeries began. The infection would clear, only to return weeks later.

“And that happened six or seven times. So over the last year I basically spent almost 80 days in the hospital and half of the time with my leg open. They would open it to clean everything.

“The doctors were always saying, 'We're going to save it. Don't worry.' But I was on the other end saying, 'Yeah, but I'm getting tired of this, you know, like, I need a solution.'”

A darkness settled over his resolve. Tom decided amputating his leg was the best solution to moving on with his life. He drowned himself in YouTube videos and began learning about prosthetics.

The doctors asked for one more chance.

A bone graft, scraped from part of his hip, facilitated partial replacement of his tibia. That was nearly two months ago. Things were looking good. Another surgery was scheduled to remove the fixator.

“They put me to sleep. And I thought, ‘I'm going to wake up without it.’ But it was still there when I woke up, and that was really hard.”

The timeline for a return to normalcy shifted once more.

Pt. 6 - The life of a bee

His beekeeping ties him to his roots. The farm, nature, creating. And like the worker bees, who have jobs they learn in their short cycle inside the hive, Tom is aware that his personal life cycle mirrors that of the bees. And now, perhaps, the work is done, and it’s time to enjoy that sweet honey. He’s had his adventures. That seed planted more than two decades ago grew larger than he imagined.

Now, at least one more surgery awaits. Followed by months of rehab. This road he has been on has dipped over the horizon. He can’t see where it ends. Or how.

When I ask if his death-defying days are over, he waivers slightly. He recently raised enough money for a 45-foot sailboat.

“It was kind of my dream boat. And the boat is at the marina here in the Azores, and it's ready to go on the next adventure.”

But what Tom knows for sure — what he understands best — is that when his personal satisfaction meter is full-tilt on nature, he’s winning. Grounded at an early age by the family farm, his connection to the outdoors — and his family’s nurturing of the land — will outlive soaring over the Alps on a paraglider. He knows the farming lifestyle will always embrace him.

“If everything was to stop, let's say, next year, because this is impossible to walk on, I would just … get on with it. So this is okay. I have a beautiful time with my family. I spend a lot of time at home, which hasn't been happening for a long time. So that's a bit different for me. And I enjoy it.”

Matthew Fults is the author of five novels, including the award-winning Mathieu James Trilogy. Its debut The Scotland Project, was named a Finalist for Best Thriller. Its sequel, Messenger for the Dead, won Action Thriller of the Year while the finale, The Consequence of Sin, is available now. Fults also wrote The Sunflower Widows and Nikolai's Secret.